On one particularly frigid morning in Brooks, Alberta, chef Martin Yan sped down the road to catch his first television appearance on a local Canadian show. Yan found himself in Canada during 1978, when he took a brief hiatus from his studies at UC Davis to help a friend open a Chinese restaurant. And he caught the eye of television producers who asked him to come down to the station for a cooking demo. But that morning, temperatures were at negative 30 degrees, and Yan was getting increasingly nervous.

“The reason why they called was because the executive chef was sick and couldn’t make it. So … I said, ‘Well, I’ve never been on television before.’ They said, ‘Well, you’ve got to come in because we love your food.’”

Despite his initial hesitation, Yan agreed to be on the show because he wanted to help promote his friend’s new business. But as soon as he pulled into the television station, Yan went from anxious to sheer panic mode.

“I put the food in the trunk and by the time I got to the station, I couldn’t even open the trunk because it was frozen,” Yan recalled. “So, we frantically asked somebody to pry open the trunk and I brought all the food out. The broccoli, asparagus, meat, and even the oil were frozen. I decided to do a frozen dinner because I said, when I was in college, most of the college kids eat frozen dinners anyway.”

Things didn’t get any better when he got in front of the camera. Television producers told Yan to relax and to just focus on the camera with a flashing red light — but the only problem was that no one told him the red light would bounce among three cameras on set.

“I was looking around and I said, ‘I’m totally confused. The red light is moving around. I don’t know which one to talk to.’ I was actually saying this live on television,” Yan said.

To say that Yan’s television career began in a frenzy would be a huge understatement, but his performance on set was exactly what charmed the TV show’s executive editor. Yan was asked to return for a second show the following week, and this time Yan made sure to keep his groceries in the back seat of his car.

A star (and catchphrase) is born

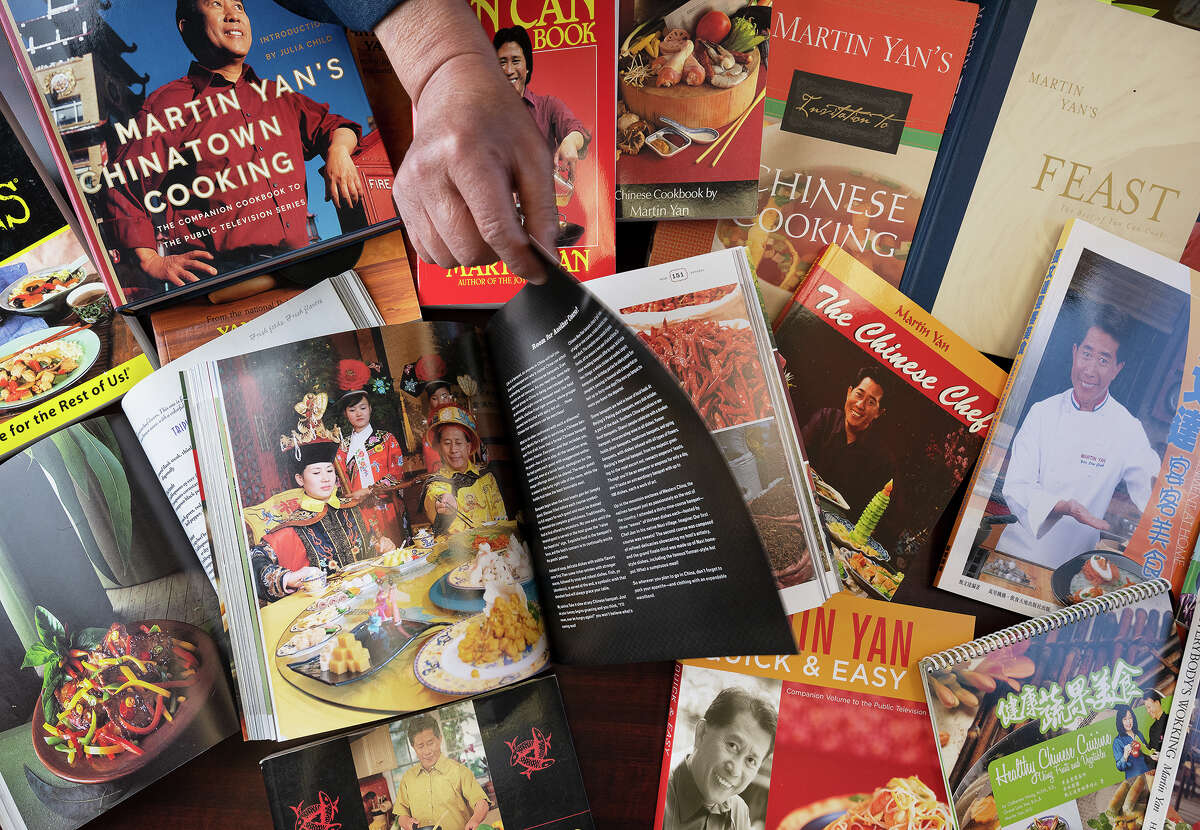

That program would become Yan’s seminal show, “Yan Can Cook,” which first aired in Canada in 1978 and later hit PBS in 1982. Yan became a pioneer for cooking Chinese food on national television, and after more than 40 years, he’s still telling viewers of “What’s for Dinner with Martin Yan” on KTSF Channel 26, “If Yan can cook, so can you.”

Yan’s onstage personality was both humorous and educational. His passion for teaching shone through, and he had a knack for convincing the audience that even they could debone a whole chicken in record time, just like the master chef himself. (You can watch his demonstration on minute 6:18 in the video below).

Yan’s career may have started in Canada, but today, he makes his home in San Mateo. When I called chef Yan a couple of weeks ago to talk about his impressive career, he sounded just as animated and welcoming as he did on the show. Throughout his profession, Yan has had numerous television appearances including, “Iron Chef America,” “Top Chef” and “Hell’s Kitchen,” and he’s also the author of dozens of cookbooks.

Yan admits that he never sought fame — despite once joking with his college roommates that he might be on television someday while they watched Julia Child’s “The French Chef.” As a student at UC Davis, Yan taught a cooking class at the university’s extension program; in his off time, he was inspired by Child’s onscreen charisma and her easy-to-follow approach to the French culinary arts.

Chef Martin Yan shares an undated photograph with Julia Child when they received an honorary doctorate degree in culinary arts from Johnson & Wales University.

Lance Yamamoto/Special to SFGATE“When I went to college, there was no cooking show on the air except two: Julia Child’s ‘The French Chef’ and Graham Kerr’s ‘The Galloping Gourmet.’ Julia Child was very entertaining [and] Graham Kerr was the same, very, very energetic. Not only were they really informative, but they were also very funny.”

Yan would take a page from Child’s approachability onset, and years later, he and Child became great friends. Yan says that he never appeared on Child’s TV show or vice versa, but he says that he would often share many of his Chinese restaurant recommendations with her.

“When PBS had special events, promotions or fundraising, we’d all get together. Julia always wanted me to take her to Chinese restaurants. She loved Chinese food.”

He also rubbed elbows with French chef Jacques Pépin, who did appear on “Yan Can Cook.” Photographs of both TV personalities still hang in Yan’s business office to this day. Yan continues to have friends in high places throughout the world and plenty of friends who are restaurateurs in the Bay Area.

Chef Martin Yan observes the photographs memorabilia seen in his office. Yan’s career launched with a cooking show in Canada in 1978 that later became “Yan Can Cook,” first airing on PBS in 1982.

Lance Yamamoto/Special to SFGATEWhy Yan can’t settle on just one Bay Area Chinese restaurant

When I ask Yan to tell me what his top favorite local Chinese restaurants are, Yan has trouble answering it in simple terms. It’s not that he isn’t willing to share the names of the restaurants to be diplomatic. He says that naming a handful is difficult because Chinese food is incredibly diverse.

“You’ve got Cantonese cuisine, Hong Kong style, Sichuan, and then you’ll have people that specialize in Shanghai and Beijing cuisine. How can you compare a seafood restaurant with a hot pot restaurant? People need to understand that Chinese cuisine is so diverse, so all-encompassing and it has so many regional flavor profiles. It is very hard to pinpoint which is the best Chinese restaurant,” Yan says.

Nevertheless, when it comes to drawing inspiration for his own cooking, Yan says he loves to head over to contemporary restaurants like Mister Jiu’s, owned by chef Brandon Jiu, or Palette Tea Garden & Dim Sum in San Mateo. If he’s in the mood for dumplings or northern-style Peking duck, Yan opts for chef George Chen’s China Live. And when he’s craving seafood, he prefers HL Peninsula Pearl or Koi Palace. Yan told me that the next evening he was going to have dinner with good friend Larry Chu, chef-owner of Chef Chu’s in Los Altos.

Yan’s own restaurant, M.Y. China, permanently closed November 2020 during the pandemic, though he says that he’s still on the lookout to possibly open another restaurant in the future. M.Y. China opened in 2012 and remained on the fourth level of Westfield San Francisco Centre for nearly 10 years before it closed. Yan says that customers were disappointed by the closure, but he said that operating a restaurant inside the mall became increasingly difficult without the possibility of outdoor dining.

“Even now, [indoor dining] is only at 25% capacity in San Francisco. You cannot survive with that kind of rent. It’s very expensive.”

And when it comes to the future of Bay Area restaurants, Yan suspects that the challenges brought on by the pandemic will have a huge role in the way people will dine in a post-pandemic world.

“I think the lifestyle and the way people eat will be changed. A lot of people will do delivery … because nobody wants to get out anymore. Even if they go out to eat, they will not eat like before. I think the pandemic is changing everybody’s perception about things. I think most restaurateurs are probably aware of the new norms… and they will maybe [have to] simplify the menu a bit.”

How Martin Yan is spending his time now

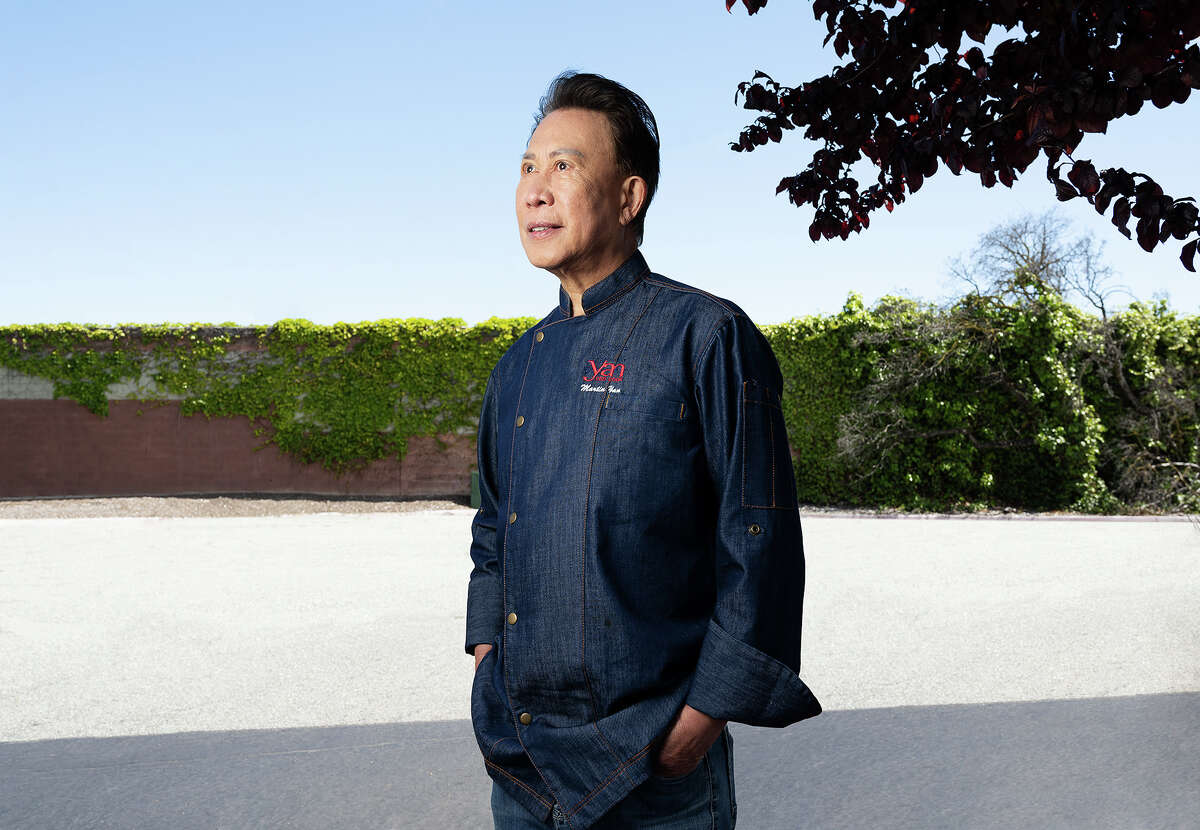

Now in his 70s, Yan remains humbled and grateful for the opportunities he’s been given. And he’s not slowing down anytime soon. The pandemic has changed the way he would normally spend his time traveling the globe for new TV projects, but it’s also given him the chance to focus on local issues he cares deeply about.

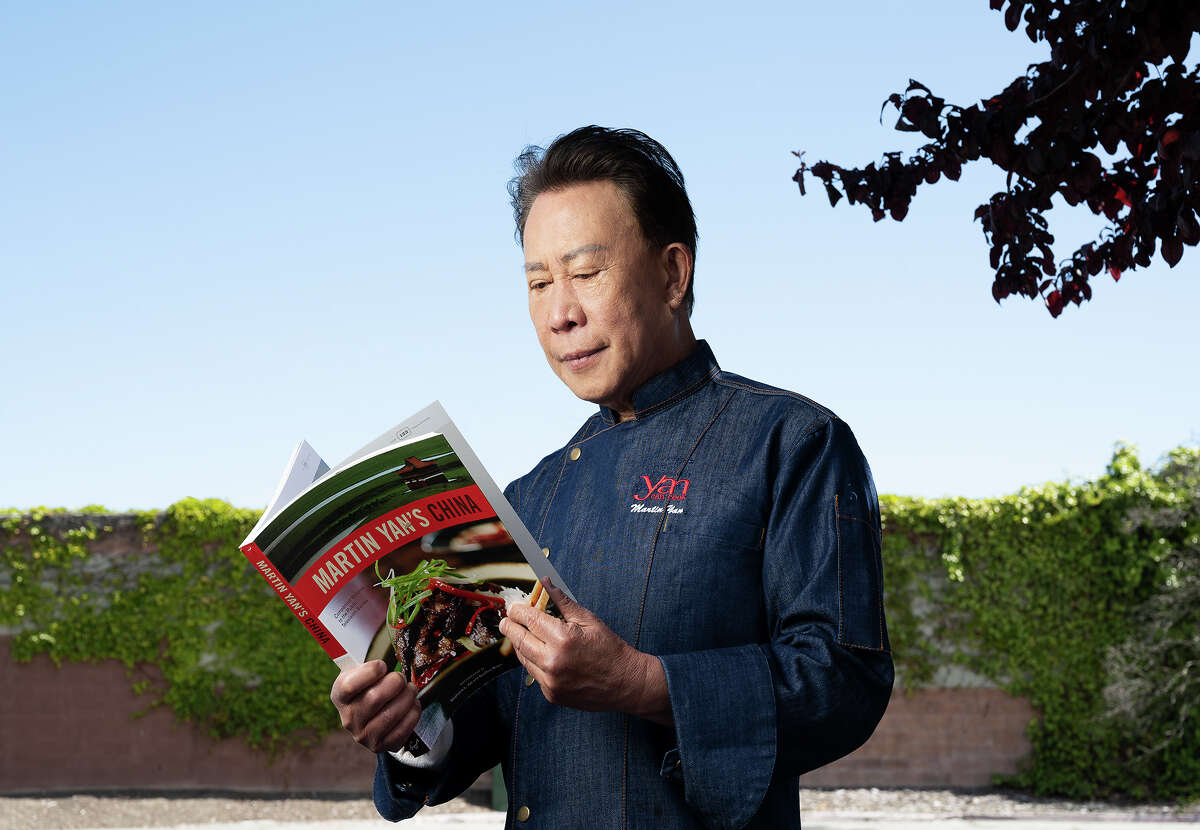

Chef Martin Yan’s career launched with a cooking show in Canada in 1978 that later became “Yan Can Cook,” first airing on PBS in 1982.

Lance Yamamoto/Special to SFGATEThe recent rise in Asian hate crimes around the Bay Area has troubled Yan, and he wants to use his platform to put an end to the violence. Part of that comes in the shape of connecting with organizations that are working to stop Asian hate, as well as raising funds at charity events.

“I’m proud to be able to give a voice,” Yan said. “I hope my career and what I do can make a little impact in the community and help people understand that we should respect everybody’s culture, heritage and that we are all individuals. And food is the best equalizer. Food is the best diffuser. Food has no international boundary.”

During the pandemic, Yan also teamed up with about 100 Chinese restaurants across the U.S. to offer free meals to frontline workers. Yan is also taking some time to reflect on his career and spend more time outside. He says he does an average of 10,000 steps around his neighborhood, and when he’s feeling especially energetic, he’ll do an extra 5,000 steps. Mostly though, he’s been spending time in his vegetable garden.

“Now I take my time. I do things that I enjoy. Sometimes you rush, rush, rush and you’re not actually going anywhere, spirituality, as well as physical. [The pandemic] gave me the chance to slow down, to reflect on life and to be able to do something for the community. I hope that in the remainder of my career I can continue to offer my love for food and cooking. [To] use this platform as an opportunity to reach out to people and let them understand and accept each other through food, culture, tradition, and heritage.”